Sheila Kohler is a South African author now living in the United States, in New York. Her latest book is a memoir, Once We Were Sisters. She is the author of thirteen books—novels, short story collections, and memoir. Below this interview is more about her latest book.

Sheila Kohler is the nonfiction judge in the inaugural Macaron Prize.

Cagibi: Hilaire Belloc, the early twentieth century Anglo-French writer and historian, wrote, “We wander for distraction, but we travel for fulfillment.” In what ways do you see yourself in this quote, or how do you interpret it?

Sheila Kohler: I think I left South Africa as a young girl not so much with an idea of either distraction or fulfillment but rather to find out who I was. I was seventeen and felt I had to leave my family, my divided country, even my own language, and go somewhere and speak a foreign tongue in order to find out what I really thought and felt about so many things. It seems contradictory and of course it did not happen overnight but in some ways taking on a disguise, hiding in the cloak of a foreign tongue, one finds one’s own unique form and voice. I sometimes give an exercise to students to write from a point of view of someone they are in conflict with and the truth has a habit of emerging more easily than if we try to put ourselves directly on the page.

Cagibi: Tell us more about your distractions—can they be fulfilling, in some ways? Or just not…

Kohler: Oh! yes! Give us distractions! At the moment I am in Paris walking the beautiful streets of the past and thinking of those who walked here before me. Often it is in the distractions that an idea or a link appears to us out of the blue which helps with our work, whatever it might be.

Cagibi: A cagibi, loosely interpreted, is a space such as a cubbyhole, or a space where you store things. Or the workspace in which authors write. For ourselves we’ve translated it as “any shelter, no matter how tiny, that allows for big imaginings to take shape.” For you, what is a space that allows big imaginings to take shape?

Kohler: Any space or almost none at all. I find I can write on airplanes or in cafes or in my own bedroom. I think it may be from bringing up small children and trying to write with them running around me or perhaps I am just good at shutting out the world around me at times. I do a lot of work on trains which I take to go to Princeton from New York and if there is a quiet car it helps, of course! Someone on a cell phone is hard to ignore!

My husband and I have recently moved to a very small apartment but the small space does not seem to have interfered with our work. We have two rooms and can establish privacy if we wish but unexpectedly I think the close proximity helps.

Cagibi: How does traveling to a new place influence your writing? In what ways do you incorporate travel experiences into your writing? And is this part of the “fulfillment” that Belloc wrote?

Kohler: There are, of course, beautiful places that find their way through the imagination into the work, but perhaps the places of our childhood remain the richest, with the imagery brighter and more original, the world transformed by the child’s receptive mind and imagination. I was very lucky growing up in such a beautiful world—South Africa, with so much sunlight and deep shadow, and with such a contrast between the beauty of the landscape and the acts of the people who inhabited the place.

Cagibi: As a writer, does traveling interrupt and interfere with your writing projects, and is this good or bad?

Kohler: It can interrupt, of course, and traveling has become more difficult today, but I have memories of sitting on airports writing when planes have been delayed, for example. Sometimes an enforced delay can be productive!

Cagibi: In just one of your works, tell us a way in which “place” influenced what you created on the page.

Kohler: I do think, if you can get the place right a lot comes from there. The place holds it all together. You can start there, wander away, and then come back again. I am writing something now about the return of two sisters to a house where they grew up after the death of the older sister’s husband. The house, the paintings, the old sofa where they have sat and talked and wept through their lives are all very useful to me as I can see the rooms in my mind and move the two women through the spaces of a house I know well.

Cagibi: Did you ever have to hide in order to write?

Kohler: Oh, yes, I’m afraid in a way writing is almost always like hiding. It enables one to leave the real world and create a fictive one where one can transform much of the real world as one likes. Of course for the writing to be any good one has to use this fictive place to find an inner truth, which may not be something that is easy to do. So often students will tell me a fascinating story about their lives and I will say, “But write that!” and they say, “Oh! I couldn’t!” I think one needs to hide in order to discover what really lies within which is a difficult task.

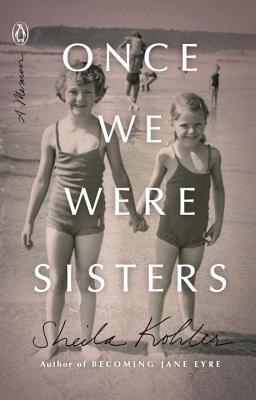

About Sheila Kohler’s Once We Were Sisters

Sheila Kohler’s latest book, a memoir, Once We Were Sisters, was published in 2017 by Penguin. From the publisher:

When Sheila Kohler was thirty-seven, she received the heart-stopping news that her sister Maxine, only two years older, was killed when her husband drove them off a deserted road in Johannesburg. Stunned by the news, she immediately flew back to the country where she was born, determined to find answers and forced to reckon with his history of violence and the lingering effects of their most unusual childhood—one marked by death and the misguided love of their mother.

When Sheila Kohler was thirty-seven, she received the heart-stopping news that her sister Maxine, only two years older, was killed when her husband drove them off a deserted road in Johannesburg. Stunned by the news, she immediately flew back to the country where she was born, determined to find answers and forced to reckon with his history of violence and the lingering effects of their most unusual childhood—one marked by death and the misguided love of their mother.

In her signature spare and incisive prose, Sheila Kohler recounts the lives she and her sister led. Flashing back to their storybook childhood at the family estate, Crossways, Kohler tells of the death of her father when she and Maxine were girls, which led to the family abandoning their house and the girls being raised by their mother, at turns distant and suffocating. We follow them to the cloistered Anglican boarding school where they first learn of separation and later their studies in Rome and Paris where they plan grand lives for themselves—lives that are interrupted when both marry young and discover they have made poor choices. Kohler evokes the bond between sisters and shows how that bond changes but never breaks, even after death.

Appears In

Cagibi Issue 2